Foreword: In December 2014, I featured a biography of San Francisco liquor dealer, Amandus Fenkhausen, a German immigrant often credited with introducing the Christmas tree to the California city. In the course of the story in passing I noted in passing his business relationship with another German named Herman Braunschweiger, shown below. Subsequently I have learned that Herman had his own story, one not so “sunny” as Fenkhausen’s, a tale involving his son, Herman Braunschweiger Jr., hereafter identified as “Junior.”

Herman Braunschweiger was born in October 1839 in Stadtkreis Braunschweiger, more commonly known as Brunswick, Germany. Although his early life has gone unrecorded, an 1890 passport application indicates that in 1859 at the age of 20 he arrived in New Orleans from Bremen on the S.S. New York, a packet that carried freight and had forty passenger cabins. He appears to have lived in New Orleans for a few years, possibly working in the liquor trade, and was naturalized a U.S. citizen there in 1868.

Herman Braunschweiger was born in October 1839 in Stadtkreis Braunschweiger, more commonly known as Brunswick, Germany. Although his early life has gone unrecorded, an 1890 passport application indicates that in 1859 at the age of 20 he arrived in New Orleans from Bremen on the S.S. New York, a packet that carried freight and had forty passenger cabins. He appears to have lived in New Orleans for a few years, possibly working in the liquor trade, and was naturalized a U.S. citizen there in 1868. By 1870 Braunschweiger had migrated to San Francisco where he later teamed up for several years with Fenkhausen as importers and jobbers of wines and liquors in a business located at the northwest corner of Front and Sacramento Streets. By 1882, he was in a brief co-partnership with E. H. Bumstead that ended in 1884 with Herman going it alone in a liquor dealership he called Braunschweiger & Co., its headquarters shown right.

By 1870 Braunschweiger had migrated to San Francisco where he later teamed up for several years with Fenkhausen as importers and jobbers of wines and liquors in a business located at the northwest corner of Front and Sacramento Streets. By 1882, he was in a brief co-partnership with E. H. Bumstead that ended in 1884 with Herman going it alone in a liquor dealership he called Braunschweiger & Co., its headquarters shown right.

Meanwhile, the German immigrant had immersed himself in family life. Shortly after arriving in San Francisco he married Elise Roper, an immigrant herself from Lower Saxony, Germany, who was six years his junior. In quick succession the couple would have three children: Edward, born in 1871; Herman Junior, 1872; and Elise, 1875. A fourth child, Frieda, would come in 1884.

As Braunschweiger was struggling hard to build his business and provide for his family, he and Elise were having increasing difficulties controlling their second son. Junior seemed cut from a different cloth than their other children. At the age of fifteen the boy ran away from home in 1888, stealing his mother’s jewelry to finance his fling. Found and brought home, Junior now 17 absconded a second time. Braunschweiger tracked him down and had him arrested on a vagrancy charge. A San Francisco newspaper told the story: “Last night the father found his son in a lodging house at No. 17 Fourth Street in company with a dissolute woman named Frankie Ray, with whom he had been living. In the lad’s possession was found a lot of valuable jewelry, which he had stolen from his parents’ house….”

Apparently unwilling to pursue criminal charges against his son and wanting him out of the clutches of Franky Ray, Braunschweiger arranged to send Junior abroad for a period. The errant boy was issued a passport in April 1890 — his occupation given as “scholar” — and by June had arrived in England. In a subsequent passport filing Junior indicated he spent the next few months traveling around the Continent and was now residing in Bremen, Germany, but planned to come back to the U.S. in “one or more” years.

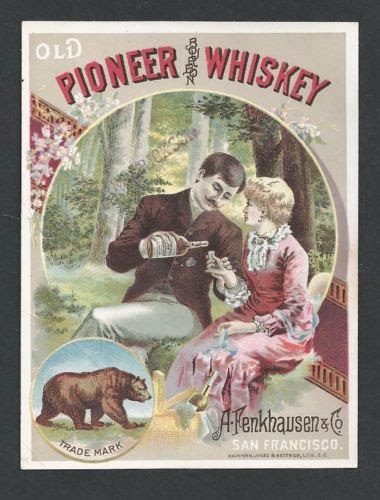

When he returned, Junior may have been contrite and more mature, leading Braunschweiger to bring him into the firm and trusting him as a traveling salesman. The young man likely carried a sample case, like the one shown here. The case held vials of Brauschweiger wines and whiskeys, including the company’s flagship labels, “Bear Grass” and “Old Pioneer,” the latter brand name acquired subsequent to Fenkhausen's death in 1893.

When he returned, Junior may have been contrite and more mature, leading Braunschweiger to bring him into the firm and trusting him as a traveling salesman. The young man likely carried a sample case, like the one shown here. The case held vials of Brauschweiger wines and whiskeys, including the company’s flagship labels, “Bear Grass” and “Old Pioneer,” the latter brand name acquired subsequent to Fenkhausen's death in 1893.  Accounts suggest that Junior was successful as a salesman, for several years traveling around California profitably for his father. But the youth could not stay out of trouble. In June 1892, he was aboard a yacht with a group of friends that embarked from Triburon, located on a peninsula that reaches south into San Francisco Bay, shown here. Among those aboard was a young lithographer, Walter H. Nitchy, who complained of being sleepy, according to testimony at the inquest into his death. Junior and others testified before a coroner’s jury that he agreed to let them throw him into the water and that he enjoyed the dip. The day following, however, Nitchy died at home of congested lungs. Medical diagnosis subsequently indicated he had existing heart and lung impairments “so weak that death could come at any time.” Junior and the others went free.

Accounts suggest that Junior was successful as a salesman, for several years traveling around California profitably for his father. But the youth could not stay out of trouble. In June 1892, he was aboard a yacht with a group of friends that embarked from Triburon, located on a peninsula that reaches south into San Francisco Bay, shown here. Among those aboard was a young lithographer, Walter H. Nitchy, who complained of being sleepy, according to testimony at the inquest into his death. Junior and others testified before a coroner’s jury that he agreed to let them throw him into the water and that he enjoyed the dip. The day following, however, Nitchy died at home of congested lungs. Medical diagnosis subsequently indicated he had existing heart and lung impairments “so weak that death could come at any time.” Junior and the others went free. That incident was dredged up by the press four years later when Junior once again made the headlines in San Francisco newspapers. This time because — and whom — the young Braunschweiger had wed. In August 1896 Junior was married in Oakland by a justice of the peace to Sadie Nicholas, a woman who not only was a dozen years older than his 24 years, but known to be a notorious brothel madam who once had been arrested for keeping her young daughter resident in her house of ill fame.

That incident was dredged up by the press four years later when Junior once again made the headlines in San Francisco newspapers. This time because — and whom — the young Braunschweiger had wed. In August 1896 Junior was married in Oakland by a justice of the peace to Sadie Nicholas, a woman who not only was a dozen years older than his 24 years, but known to be a notorious brothel madam who once had been arrested for keeping her young daughter resident in her house of ill fame.

When contacted by reporters about the nuptials, Braunschweiger seemed resigned to the situation. “As he is of age, and they are legally married,” the liquor dealer is quoted saying, “I cannot see what I can do about it.” With further reflection, however, the father changed his mind, swore out a warrant and had Junior arrested on the grounds that he was insane and required institutionalization.

The case quickly came before a San Francisco judge. Junior’s mother testified that her son had an “over-fondness” for drink and that she considered him “weak minded,” a mental weakness made worse by drinking. She revealed that in May Junior had gone to a “Home of the Inebriates” for treatment for the liquor habit. Briefly he had kept straight until he again began to drink heavily and during this spree had married Sadie Nichols. On the witness stand his father, according to the press, “reluctantly acknowledged that there was a taint of insanity in the family, and said he desired to have his son placed in some institution where he could be taken care of.”

The case quickly came before a San Francisco judge. Junior’s mother testified that her son had an “over-fondness” for drink and that she considered him “weak minded,” a mental weakness made worse by drinking. She revealed that in May Junior had gone to a “Home of the Inebriates” for treatment for the liquor habit. Briefly he had kept straight until he again began to drink heavily and during this spree had married Sadie Nichols. On the witness stand his father, according to the press, “reluctantly acknowledged that there was a taint of insanity in the family, and said he desired to have his son placed in some institution where he could be taken care of.”

The new Mrs. Braunschweiger Jr., a.k.a. Sadie Nichols, told the judge a different story. She said it was not a hasty marriage and that the matter had been talked over between herself and her new husband several times. She did not believe him insane and had never noticed anything to indicate that such was a fact. The judge, after listening to the testimony, ordered Junior released: “His Honor said that, although the young man might be irrational when drinking, he was no fit subject for an insane asylum.”

Despite walking out a free man, Junior could not stay out of trouble. After the trial the Braunschweiger family cut off all financial assistance to him. The couple soon was hard pressed for money and turned to Sadie’s niece, Ella Holstein, for help. Their constant demands soon wearied Ella and upon their visitation to her apartment in early September she refused any further funds. Whereupon Junior is said to have seized her by the throat and choked her. Saved from further injury by the interposition of the landlady, Ella swore out an assault warrant. The headline in the San Francisco Examiner read “Braunschweiger in Trouble Again, Attacks Wife’s Niece.”

Those scandals erupted while Braunschweiger faced a critical time in his business ventures. At the equivalent cost of $880,000 today, he had committed to constructing a new building for his liquor house on Drumm Street adjacent to his California St. address. It was a spacious edifice, shown here, five stories and a basement with large glass windows for showing his liquor products. The building had two entrances, one directly into the store, another leading to a staircase to the upper floors and basement, that also were served by an electric passenger and freight elevator.

Those scandals erupted while Braunschweiger faced a critical time in his business ventures. At the equivalent cost of $880,000 today, he had committed to constructing a new building for his liquor house on Drumm Street adjacent to his California St. address. It was a spacious edifice, shown here, five stories and a basement with large glass windows for showing his liquor products. The building had two entrances, one directly into the store, another leading to a staircase to the upper floors and basement, that also were served by an electric passenger and freight elevator.

At the time Braunschweiger also was expanding his marketing reach to other parts of the West and even as far away as Hawaii. He also introduced and was attempting to market successfully new proprietary brands, "California Club,” "Extra Pony,” ”Golden Chief,” "Golden Cupid,” "Golden Rule,” ”Bear Valley,” "Golden Rule XXX Sour Mash,” “Kentucky Bourbon Whiskey,” "Oak Valley Distilling,” Brunswick Extra Pony Pure Bourbon Whiskey,” "Tennessee White Rye,” and "Silver Wedding.”

It is not entirely clear what the future brought for Junior. It would appear that the battery charges were dropped. He and Sadie divorced, an event that may have smoothed his welcome back into the Braunschweiger fold and even working again at the liquor firm. The evidence is in a certificate from his second marriage. There Junior is described as a “commercial traveler,” his former employment. In December 1899 he was recorded marrying Louise Rogers, the daughter of an Irish immigrant laborer. The nuptials took place before a justice of the peace in a hamlet in Washington State, more than 800 miles from San Francisco, indicating some element of secrecy.

Meanwhile, Braunschweiger continued to operate his liquor business with success and prosperity. In October 1905, however, he sickened and died in his residence at 2216 California Street, a few days short of his 66th birthday. His funeral services were held at the Masonic Temple under the auspices of the Herman Lodge to which he had belonged. He was cremated and his ashes deposited in the San Francisco Colombarium, next to his wife who had died in 1899. Herman’s urn is shown here.

Meanwhile, Braunschweiger continued to operate his liquor business with success and prosperity. In October 1905, however, he sickened and died in his residence at 2216 California Street, a few days short of his 66th birthday. His funeral services were held at the Masonic Temple under the auspices of the Herman Lodge to which he had belonged. He was cremated and his ashes deposited in the San Francisco Colombarium, next to his wife who had died in 1899. Herman’s urn is shown here.

Given his reckless lifestyle it probably is no wonder that Junior died only four years after his father, passing at 37 years old in June 1909. He was still married to Louise but no children are recorded. As a sign of this “prodigal son” having reformed and been welcomed back into the Braunschweiger fold, Junior’s ashes are also in the San Francisco Colombarium, occupying a niche not far from his parents.

Note: Much of the information for this post was gathered from San Francisco newspaper stories that chronicled the Braunschweiger family and their errant son. Genealogical sites provided important data and images; other information and images were obtained from websites Western Whiskey Gazette and Ferd Meyer’s Peachridge Glass.