John was the elder of the two brothers, born in May 1850 in New Orleans to Irish immigrants Patrick and Bridget (Burke) Whallen. Soon after the family moved to Maysville, Kentucky, and then settled near Covington. In 1862 at age 11, John enlisted in the Southern Army. The Confederate Veteran Magazine of 1908, called him “the youngest Confederate veteran in the United States,” and told this story: “...When some youths of the neighborhood formed a party to cast their fortunes with the South, Whallen who was well grown for his age and of most adventurous spirit, persuaded them to accept him. On their first start a band of home guards who had learned what they were about undertook to intercept them. There was a sharp brush, and Whallen shot one man, wounding him seriously.”

Joining the 4th Kentucky Cavalry, John chiefly saw duty in Southwestern Virginia and although he participated in few big battles, his outfit was engaged in countless skirmishes with Union troops and bushwhackers. He was credited with saving the life of his commanding officer by holding off a band of marauders until help arrived. Shown here as a Confederate soldier, he served three years until the South surrendered and was mustered out at the age of 14. Subsequently he was singled out by the Kentucky Cavaliers in Dixie organization for its “Legion of Honor” and called “a superbly brilliant youth, model soldier and graceful courtier in any society.” The Daughters of the Confederacy gave him the “Cross of Honor,” its highest award. John also would become a “Kentucky colonel” and carry that honorific for the rest of his life.

John Whallen’s charm and charisma would be his lifetime hallmark, although details are scanty about his immediate post-war activities. One account says he did detective and police duties in Cincinnati and worked on the railroad. He also clearly was gaining experience in business, likely in the entertainment field. About 1876 he moved to Louisville to work and four years later had accumulated sufficient capital to open the Buckingham Theater on West Jefferson Street. He would go on to own several theaters including the Grand Opera (later Savoy), shown here. Although John undertook legitimate theatrics, his made his money with burlesque, notorious because of its ties to prostitution and gambling.

As his business interests increased, John called his brother James, seven years his junior, to join him in Louisville as his partner. Shown here, James proved to be a valuable ally. The Kentucky Irish American newspaper proclaimed that when “the Whallens buy a pair of shoes, one belongs to Jim and the other to John.” It was the older brother, however, who managed the Whallen interests.

Meanwhile, John was not finding his partnerships in marriage as successful as that with his brother. Whether the result of divorce or death, John Whallen was married three times. His first wife was Marian Hickey who gave him three children, two girls, Ella and Nora, and a boy, Orie. By 1800, however, at age 29, he was married again to a woman named Sarah Jane. She had been born in Tennessee of a French father and Irish mother. The 1880 Census did not indicate any children living with them. By the time of the 1900 census Sara Jane was gone and Whallen was married to Grace Edwards Goodrich, whose roots were in New York State. She had one daughter whom John adopted.

Meanwhile, John was not finding his partnerships in marriage as successful as that with his brother. Whether the result of divorce or death, John Whallen was married three times. His first wife was Marian Hickey who gave him three children, two girls, Ella and Nora, and a boy, Orie. By 1800, however, at age 29, he was married again to a woman named Sarah Jane. She had been born in Tennessee of a French father and Irish mother. The 1880 Census did not indicate any children living with them. By the time of the 1900 census Sara Jane was gone and Whallen was married to Grace Edwards Goodrich, whose roots were in New York State. She had one daughter whom John adopted.In the 1900 census, John Whallen gave his occupation as “capitalist.” Indeed, the brothers were branching out in their business activities. John became half owner of the

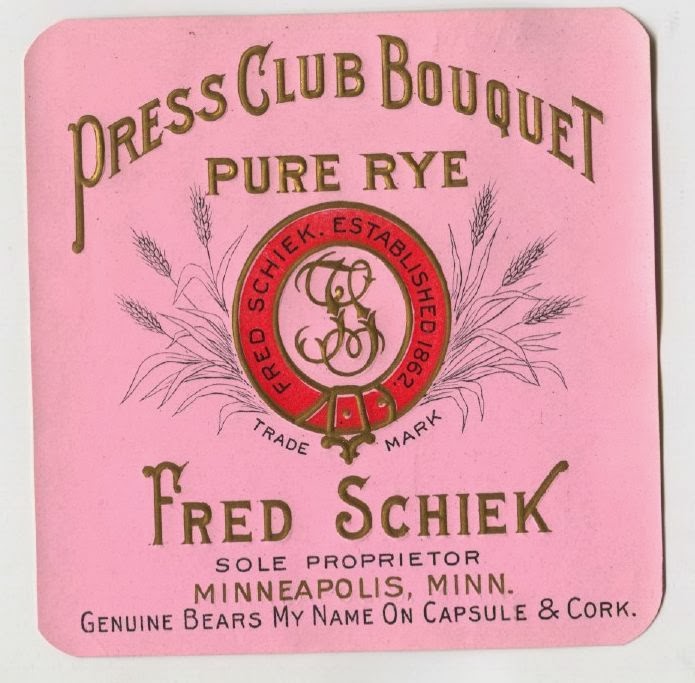

Whallen & Martell Mammoth Company. He also was a principal in a national vaudeville circuit. Perhaps appreciative of the money being made in Louisville by the whiskey barons, about 1902 the brothers established their own whiskey wholesale and retail business. The Whallens advertised “mail orders our specialty,” a trade that was booming as states and localities were going “dry” but shipped-in liquor was still legal. Locating their business at 219-227 West Jefferson St., Whallen Brothers were “rectifiers,” that is, blending whiskeys to taste, then bottling, labeling, and selling them.

Whallen & Martell Mammoth Company. He also was a principal in a national vaudeville circuit. Perhaps appreciative of the money being made in Louisville by the whiskey barons, about 1902 the brothers established their own whiskey wholesale and retail business. The Whallens advertised “mail orders our specialty,” a trade that was booming as states and localities were going “dry” but shipped-in liquor was still legal. Locating their business at 219-227 West Jefferson St., Whallen Brothers were “rectifiers,” that is, blending whiskeys to taste, then bottling, labeling, and selling them. Their flagship brand was Spring Bank Whiskey, advertised here on a paperweight. In fact, many of

+PW.JPG) the Whallen’s products bore the name, including “Spring Bank High Ball Split,” “Spring Bank Lithia High Ball Splits,” and “Spring Bank Lithia Cherry Phosphate,” all trademarked in 1903. John named his sprawling Louisville estate “Spring Bank Park.” As on the jug shown here, the Whallens pushed the medicinal value of

the Whallen’s products bore the name, including “Spring Bank High Ball Split,” “Spring Bank Lithia High Ball Splits,” and “Spring Bank Lithia Cherry Phosphate,” all trademarked in 1903. John named his sprawling Louisville estate “Spring Bank Park.” As on the jug shown here, the Whallens pushed the medicinal value of  lithia water, a mineral water with purported health benefits, particularly for the kidneys and liver. Whallen beverages also came in glass bottles.

lithia water, a mineral water with purported health benefits, particularly for the kidneys and liver. Whallen beverages also came in glass bottles.It was neither rectified whiskey nor phony medicinals, however, that thrust the Whallens into the political arena. It was the need to protect their entertainment business. Having abandoned serious theater for shows featuring scantily-clad women who provided “female companionship” and off-stage services to male patrons. Although the Whallens gave free passes to members of the Louisville police force and usually were repaid with a blind eye, in 1880 an undercover police taskforce raided the Buckingham Theater and closed down a

production called “Female Bathers in the Sea.” A Louisville grand jury of thirteen men, all workers or unemployed, were unimpressed by the evidence, however, and refused to indict the Whallens on a charge of obscenity.

production called “Female Bathers in the Sea.” A Louisville grand jury of thirteen men, all workers or unemployed, were unimpressed by the evidence, however, and refused to indict the Whallens on a charge of obscenity.John immediately recognized that his theatrical enterprises would be under constant pressure from the more respectable elements in Louisville. By the mid-1880s the upstairs “Green Room” in the Buckingham Theater had become the hub of local Democratic politics and John was dubbed the “Buckingham Boss.” Others called him “Boss John” and some “Napoleon.” In 1885 he engineered the election of Louisville’s mayor and for his efforts was rewarded with being named Chief of Police. No more surprise raids on Whallen theaters. One biography asserted that Whallen “... influenced every Louisville and statewide Kentucky election for the rest of his life. In addition to bribing officials and controlling assistance programs, at his peak Whallen controlled the awarding of 1,200 city patronage jobs.”

The Pulitzer-prize winning journalist Arthur Krock recalled Whallen’s dominance of Louisville politics in his memoirs, describing the Buckingham Green Room as “the political sewer through which the political filth of Louisville runs.” Not all in Louisville shared that attitude. John was noted for his charitable work, providing food to the out-of-work and assisting the poor. As a result he was popular among immigrants, blue collar workers, and Catholics. They saw him as their champion against the Louisville establishment.

The Pulitzer-prize winning journalist Arthur Krock recalled Whallen’s dominance of Louisville politics in his memoirs, describing the Buckingham Green Room as “the political sewer through which the political filth of Louisville runs.” Not all in Louisville shared that attitude. John was noted for his charitable work, providing food to the out-of-work and assisting the poor. As a result he was popular among immigrants, blue collar workers, and Catholics. They saw him as their champion against the Louisville establishment.Even as his power increased, however, John was to know multiple tragedies. His third wife, Grace, died in the early 1900s. Then, in December 1909, his only son, Orie, died at St. Mary and Elizabeth Hospital after a short bout of pneumonia. Orie had been deputy clerk of the Circuit Court and later worked for his father as superintendent of the Spring Bank Lithia Water Company. John was devastated with grief and it was his brother James who claimed the young Whallen’s remains and arranged for the wake, funeral and burial.

John Whallen would live four more years, dying at age 63 while still wielding political influence in Louisville. With his passing in 1913, the reins of the Whallen machine were handed to James. The brother, although he had been important in the rise of the family fortunes, was unable to maintain the power of the political organization John had built. James lacked the charisma of his older brother and gradually the power of the Whallen political machine faded. James lived another 17 years, dying in 1930. Partners in life, the brothers were reunited in death in a mausoleum bearing their name in Louisville’s St. Louis Catholic Cemetery. Their caskets are stacked one above the other. Appropriately, John’s is on top.

The Whallens left few legacies of their once dominant role in Louisville. John’s Spring Bank Park estate became public open space known as Chickasaw Park. James’ mansion at 4420 River Drive was razed in 1947 and became the site of Bishop Flaget High School. One remaining relic is a stained glass window in the mausoleum. It features a wreath in which are intertwined two letters, “W” and “B”: the Whallen Brothers.