Although McCulloch was born in Missouri in 1860 (some records say 1861), he was from a Kentucky family whose roots were in Ireland. For early on he appears to have lived in Owensboro, Daviess County, and was practiced in the whiskey trade. In November of 1884 McCulloch, about age 24, married Jessie Holmes, a local girl and the daughter of Margaret and Thomas Holmes. Their first child was born a year later and the couple would go on to have seven children.

During these early years McCulloch was working as an employee of the U.S. Internal Revenue Service as a gauger, an official who tested the alcoholic strength of distilled whiskeys. It was a political job in a Republican administration and he was a party member. With his rapidly growing family, McCulloch may have decided that government pay was insufficient. He had worked at a distillery on the Green River about one mile below Owensboro and he purchased it in 1888.

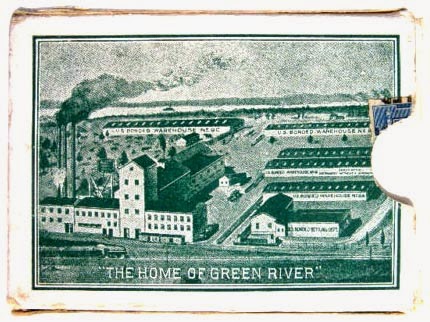

During these early years McCulloch was working as an employee of the U.S. Internal Revenue Service as a gauger, an official who tested the alcoholic strength of distilled whiskeys. It was a political job in a Republican administration and he was a party member. With his rapidly growing family, McCulloch may have decided that government pay was insufficient. He had worked at a distillery on the Green River about one mile below Owensboro and he purchased it in 1888. McCulloch incorporated his business in 1900, changing the name to the Green River Distilling Company. He immediately set about upgrading the facility. Insurance underwriter records for 1892 indicate that most of the distillery was new and had a single frame warehouse with a metal or slate roof, located 150 feet south of the still. Over time McCulloch continued to upgrade facility, eventually building two U.S. bonded warehouses under the “Bottled in Bonding” legislation. Those warehouses are the two low buildings at the back of the property, shown below. A Louisville Courier-Journal reporter described them: “His warehouses are of peculiar and costly construction, built well off the ground, closely floored, with only three tiers to the rick, low metal roof, thickly studded with skylights, every barrel at some time in the day receives its share of light and air.” McCulloch was proud of his participation in the government program and featured it prominently in his merchandising.

Another McCulloch strategy was entering his whiskey into competition at world fairs and expositions. In 1893, he won a medal for excellence at the 1893 Chicago Columbian Exposition, a major prize. He also took his liquor overseas, winning a gold metal for quality at the Paris Exposition of 1900 and the “grand prize” at the 1905 Exposition Universelle de Liege, Belgium. Domestically he won a

grand prize at the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition in Portland, Oregon, at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, and the Jamestown Tercentennial Exposition in Norfolk, Virginia. Often his display was only a plain glass case with hundreds of bottles on it, left unattended. It was enough, however, to garner a prize for Green River, each award advertised widely by McCulloch.

grand prize at the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition in Portland, Oregon, at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, and the Jamestown Tercentennial Exposition in Norfolk, Virginia. Often his display was only a plain glass case with hundreds of bottles on it, left unattended. It was enough, however, to garner a prize for Green River, each award advertised widely by McCulloch.

The Colonel prominently featured his family in his vigorous advertising of his Green River Whiskey, his flagship brand. He pictured five of his children about 1897. At left, the boy hugging the baby is his eldest son, Wendall. The baby is his brother, Charles. Below them are two other brothers, on left is John Wellington, Jr. and on right, Hugh. Standing at right is his daughter and the oldest child, Martine.

McCulloch also became noted for another image that epitomized Green River whiskey. It was of a black man dressed in a top hat, vest and coat with patches on his britches. He is holding a horse with a large jug of Green River strapped to its side. In the distant background is an image of the distillery.

The Colonel used this image over and over. Above it is seen on a trade card. It was replicated as a gilded chalk statue, shown here, as well as a saloon sign, a lighted back bar item, a watch fob, a ink blotter, a good luck token a deck of cards and other giveaway items.

The Colonel used this image over and over. Above it is seen on a trade card. It was replicated as a gilded chalk statue, shown here, as well as a saloon sign, a lighted back bar item, a watch fob, a ink blotter, a good luck token a deck of cards and other giveaway items. Some authors have seen this image as having racist overtones, but that opinion appears erroneous. The inspiration reportedly was a story told to McCulloch, a Kentuckian whose family had opposed slavery. According to the tale, a lengthy rainstorm disrupted liquor supplies arriving at local Kentucky tavern and the bar had run dry. Suddenly an African gentleman, braving

the gale, appeared in town to deliver Green River Whiskey aboard his mule. Suddenly the rain stopped and a rainbow appeared. The thirsty crowd cheered and celebrated for days. To me, the black man shown on the joker card looks anything but a racial stereotype. McCulloch likely wanted it that way.

the gale, appeared in town to deliver Green River Whiskey aboard his mule. Suddenly the rain stopped and a rainbow appeared. The thirsty crowd cheered and celebrated for days. To me, the black man shown on the joker card looks anything but a racial stereotype. McCulloch likely wanted it that way.Although Kentucky was deeply divided on the question of secession both during and after the Civil War, McCulloch was an unabashed Unionist. In 1895 when the first Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.) “Encampment, an organization of Union soldiers, was held in Louisville, McCulloch was quick to issue thousands of bottles of Green River with a souvenir label and sold 13,000 of them to men from all over the United

States. The Courier-Journal praised him for the effort, lauded the quality of his products, and concluded “doubtless thousands of old soldiers will leave Louisville, ready to endorse his whiskey anywhere.” This gesture may have contributed to McCulloch being given a major contract to supply whisky to the U.S. Public Health and Marine Hospital Service several years later, a credential that he advertised widely.

States. The Courier-Journal praised him for the effort, lauded the quality of his products, and concluded “doubtless thousands of old soldiers will leave Louisville, ready to endorse his whiskey anywhere.” This gesture may have contributed to McCulloch being given a major contract to supply whisky to the U.S. Public Health and Marine Hospital Service several years later, a credential that he advertised widely.

Meanwhile, the Colonel was playing a major role in the Republican Party of Kentucky and the nation. Always an active member of the state party and a delegate to the National Nominating Conventions, about 1912 he was elected as the member of the National Committee for the State of Kentucky, a singular honor. It was not without controversy, however. Kentucky Republicans increasingly were being dominated by Prohibitionists who took a dim view of a distiller like McCulloch. He also drew fire from the “Wets.” Although

McCulloch upheld liquor interests in Republican forums, he was criticized for continuing to raise money for the party, one that ultimately declared for state and national prohibition.

McCulloch upheld liquor interests in Republican forums, he was criticized for continuing to raise money for the party, one that ultimately declared for state and national prohibition.Among McCulloch’s other activities was being a member of the board of directors of the Great Southern Fire Insurance Company of Louisville. This office was particularly ironic because in August, 1918, the Green River distillery caught fire. As the Owensboro Daily Messenger headlined: “In Three Hours Every Building of Big Concern is Reduced to Piles of Ashes.” Although portions of three warehouses were saved, McCulloch lost 18,000 barrels of aging whiskey. The loss was estimated at $3,000,000 ($45,000,000 in today’s dollar) and the greatest conflagration up to that time in Owensboro.

Another headline proclaimed: “Col. McCulloch Returns to Find Green River Gone.” Undaunted, he soon rebuilt and continued producing his distillery for a short time until he recognized that the onset of National Prohibition would shut him down. He shipped off most of his stock, much of it to the Federally controlled “concentration warehouse” at the Old Taylor facilities in Woodford County. There it was bottled “for medicinal use” under the Green River label by the authorized American Medicinal Spirits Company.

John W. McCulloch did not live to see Prohibition repealed. At the age of 67 he died in near Owensboro. He was buried at the Mater Dolorosa Catholic Cemetery there while his wife, Jessie, children, grandchildren grieved by his graveside. His headstone lies beneath a large obelisk with a cross at the base and “McCulloch” emblazoned in large letter. Other family members are buried nearby.

During Prohibition the distillery McCulloch built had been demolished, but the family continued to own the land and with Repeal rebuilt the facility and began to produce Green River whiskey. The revived distillery continued to be a family affair. It was incorporated by John W. McCulloch Jr. in December 1933. The heirs, however, found the whiskey trade difficult and were in business only a short time. They sold the Green River label to Old Tyme Distillery of New York with the whiskey produced at the A. B. Chapeze plant in Bullett County, Kentucky.

Although John McCulloch is gone, the whiskey he initiated remains of interest because of the artifacts he created. Recently the blue and white mini-jug shown above sold at auction at $1,025. An original watch fob is worth enough that it has been counterfeited. In addition, there are thousands of other artifacts out there to remind us of the Kentucky colonel who gave us a wealth of items by which to remember him and Green River whiskey.

Owensboro is pretty far from the Green River, the distillery today is back up and running under the Green River Label....on the Ohio River. Interesting to note that maybe the Green River is a better selling name than the Ohio River ...hmmm. Anyone?

ReplyDeleteIt actually was moved due to the poor quality of travel on the narrow and windy band that is green river . He found the Ohio River to be much wider and easier for shipping his product . However green river name was likely to have remained the actual name due to it having a better ring to it as you mentioned . 😉

DeleteAnon 2: Thanks for adding a very valuable piece of information. Most appreciated.

DeleteAnon: Good observation.

ReplyDeleteDo you know the value on the round jug?

ReplyDeleteAnon: Somehow I saw your inquiry only recently. Have no idea of the value of the jug you indicate. Both have value and prices of pre-Pro whiskey jugs have escalated sharply in recent months. Check eBay.

ReplyDelete