He called himself “doctor” but when and how he achieved medical training is something of a mystery. What we do know of Robert Polk Drake is that by opening saloons and a distillery he openly mocked the prohibitionists of Madisonville , Kentucky, and the “local option” laws they had enacted. Although “dry” forces eventually shut Drake down, it was not before he had become rich.

Drake’s story was well told by Katherine Gramlin in her 2018 master’s thesis at Florida State University, the primary reference for this post. Because Kentucky for so long has been considered the prime source of America’s best whiskey, it may be hard to understand that the prohibition movement, because of the state’s predominantly Protestant population, was stronger than in some states with few or no distilleries.

A Prohibitionist Party organized in 1887 in Madisonville was able to push through a number of laws on alcohol. It was decreed that all saloons or taverns must be located at least a half mile from a church or other place of worship. Existing “watering holes” would have to move or pay a penalty every three months. Many relocated to Main Street, shown here. In addition, judicial approval was required for any new establishment. Higher performance bonds and taxes also had been imposed. Saloon proprietors by law were required to maintain a trough for watering their customers’ horses.

Perhaps the most bizarre ordinance stipulated that sales for off-site use be in gallon-sized containers. While some have seen the requirement as an effort by prohibitionists to encourage drinking at home rather than in a saloon, my instinct is that they believed a heavy gallon ceramic jug would have to be carried home to drink, but half-pint or pint glass flasks could be tippled anywhere, including public places.

“Doc” Drake sized up those restrictions and decided the risk of entering the liquor trade was worth the gamble. A local boy, he was born on February 14, 1849, in Hopkins County, of which Madisonville is the seat. He was the second son of Thomas Drake, a Virginia farmer who had moved to Kentucky about 1827 and Antha “Annie” Coleman Drake, born in the state. Robert’s early learning has been described as “a good English education.”

Drake’s medical training has not been documented. In the 1800s one could claim the title of physician without having attended medical school by serving an apprenticeship with a local doctor. To pay for his training and upkeep, the apprentice would do menial jobs around his mentor’s office. He also watched procedures performed in the office and would accompany the doctor on house calls. In time, an apprentice would be allowed to attempt certain medical procedures and eventually be recognized as a doctor in his own right. I have located a Madisonville press item about an individual “wounded, was carried to the residence of Dr. R. P. Drake and treated nine weeks, then sent home.”

Nonetheless, in the early 1890s, as he entered middle age, Drake decided that rather than pushing pills for a living, he would make and sell liquor. In unabashed defiance of Madisonville’s “dry” advocates, he opened a saloon on North Main Street, located an appropriate distance from local churches. It proved to be so profitable that he decided to prod the prohibitionists further, opening another saloon on Center Street in what had been a ladies’ hat shop.

Drake soon decided that making his own whiskey was more lucrative than just

Drake soon decided that making his own whiskey was more lucrative than just

pushing drinks over the bar for nickels and dimes. In 1895, he bought land on Onion Hill, named for its strong, lingering scent. Located just outside the Madisonville city limits, the site included two springs that fed a small watercourse known as Flat Creek. Those water sources were critical to Drake’s effort to erect a distillery. Construction was completed by March 1896 and he immediately began production.

By Kentucky standards, Drake’s was a decidedly small distillery, producing only about 28 gallons a day, the rough equivalent of half a barrel. Assuming that the distillery produced whiskey every day allowed (never on Sundays), the yearly output was no more than about 165 barrels. Drake’s equipment included a steam boiler, mentioned in his will. Also shown here are a doubler and copper pipes used in distillation that are on display at the Hopkins County Historical Society Museum. The equipment is assumed to be from Drake’s facility.

By Kentucky standards, Drake’s was a decidedly small distillery, producing only about 28 gallons a day, the rough equivalent of half a barrel. Assuming that the distillery produced whiskey every day allowed (never on Sundays), the yearly output was no more than about 165 barrels. Drake’s equipment included a steam boiler, mentioned in his will. Also shown here are a doubler and copper pipes used in distillation that are on display at the Hopkins County Historical Society Museum. The equipment is assumed to be from Drake’s facility.

The reaction of Madisonville’s prohibitionists to a distillery on their border has gone unrecorded, but it must have rankled. Drake obviously did not care. He produced whiskey for his own saloons and had some to sell others. Over that period his gallon ceramic jugs bore several names, including “The R.P. Drake Distillery,” “The Twin Springs Distillery,” and “Turner Springs Distillery.” The one shown here from the Hopkins museum reads “Old Hickory Distillery” on the base.

The reaction of Madisonville’s prohibitionists to a distillery on their border has gone unrecorded, but it must have rankled. Drake obviously did not care. He produced whiskey for his own saloons and had some to sell others. Over that period his gallon ceramic jugs bore several names, including “The R.P. Drake Distillery,” “The Twin Springs Distillery,” and “Turner Springs Distillery.” The one shown here from the Hopkins museum reads “Old Hickory Distillery” on the base.

For reasons yet unexplained, Drake maintained his distillery for only 14 months before shutting it down. Perhaps he was dissatisfied with the quality of his product. Making whiskey is a tedious and delicate process. Many things can go wrong in distilling that render the results undrinkable. Drake continued to operate his two local saloons and opened a third in Evansville, Indiana, about 50 miles due north of Madisonville. He may have assumed (correctly) that Evansville would remain reliably “wet” even if his home town banned liquor.

With the wealth from his liquor pursuits, Drake also was investing elsewhere. Hopkins County was part of the Western Kentucky coal fields. In 1896 Drake announced he had opened a new mine near the railroad line about a mile and a half from Madisonville. Claiming the coal seam to be 38 inches thick, he advertised that his “work was done with a view to testing the coal for parties who wish to lease.” In other words, he was speculating, not mining himself. At the same time the “Doc” was investing in a local bank and in real estate. The latter included farmland, office and apartment buildings, a “colored housing” development, and a rooming house available specifically to members of the Presbyterian church.

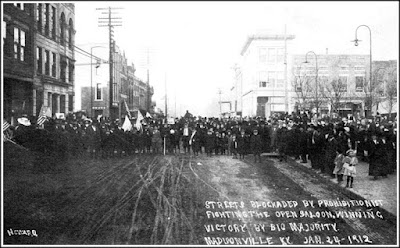

If Drake thought this outreach toward the Presbyterians would soften prohibitionist sentiments, however, he was mistaken. In 1912 local “dry” forces were able to enact by “local option” a complete ban on alcohol sales. Shown above is a marvelous photograph of an event of civil disobedience by prohibitionists in Madisonville as men, women and even small children blocked Main Street demanding that saloons be closed. The caption reads: “Streets blockaded by prohibitionist fighting the open saloon, winning victory by big majority. Madisonville Ky., Jan 24, 1912.”

Although Drake was forced to shutter his two saloons, he remained a major figure in Madisonville. Ms. Gramlin observes: “While he never served in office, Drake did use the influence of his wealth and businesses to ensure the future success of his ventures. By strategically locating the majority of his businesses downtown, buying stock in influential banks, gaining the favor of local churches by renting homes and apartment spaces to congregation members, and renting farmland and equipment to county farmers, Drake ensured that he had his thumb in every pot. He was an influential and powerful man in Hopkins County.”

Drake’s personal life, however, was not without its vicissitudes. At the advanced age of 43, in 1892 he married Willie N. Richardson, 17, in Robertson, Tennessee. In addition to the age disparity, there was some indication of haste. The wedding occurred on February 2; the marriage license was issued after February 21. The couple’s first child, Lorenzo “Loren”, was born five months later. Several years later a second son, Owen, died in infancy. As a doctor, not being able to keep his child from dying must have been extremely painful for Drake.

The relationship between the father and his son Loren appears to have been strained. The breach is evident in the will “Doc” Drake made on February 2, 1916, just days before his death. In it he left the bulk of his extensive properties to Loren but only as a caretaker for his grandchildren, Robert, then two years old, and Mary, an infant. The will stipulated that his son was to have “no power of authority to sell, convey or dispose of said property in any way or manner” but must maintain the property for the children “to be theirs absolutely.”

His wife Willie, as administrator of the estate, could sell property but the proceeds also were directed to Robert and Mary. Drake left his son 150 acres of farmland in Hopkins County with a house on it. That Loren could sell it but none of the proceeds were to be used to pay off the son’s debts “in any manner.” Once again all proceeds were to be passed on to the grandchildren. Thus was expressed a father’s apparent displeasure with a son.

Drake’s will was completed and filed only two weeks before his death, although he apparently had been under a doctor’s care since the previous March. The diagnosis on his death certificate was “tuberculosis of throat and lung.” Dead at 67, Drake was interred in Slaughters Cemetery in Webster County where his parents and other relatives were buried. Shown here, Drake’s is one of the largest memorials on the grounds, unusual because the statue of Jesus it contains is looking away from the grave. The monument records the deceased as “Dr. R. P. Drake.” Wife Willie is not buried with him.

Although the story of Robert Drake and his tussle with prohibition is not unique, it illustrates the “dry” pressures brought against alcohol production and sales in Kentucky, despite the state being world famous for its whiskey. By navigating around Madisonville’s “dry” laws for more than 20 years, however, a canny operator like “Doc” Drake was able to a build a fortune.

Notes: In researching the story of a medical doctor who owned saloons and, at least for a time, distilled whiskey, I almost immediately became aware of Ms. Gramlin’s dissertation. My efforts to locate her to for permission to quote her material and use her photos have not been fruitful, although I have emailed to an address she used and called telephone numbers listed to her. Perhaps a reader will see this post and alert her to my efforts.

Thank you Jack, always great content

ReplyDelete