Foreword: National Prohibition, banning all liquor distilling and sales throughout the entire United States, was the law of the land from 1920 until 1934. During that period three well known American authors, one woman and two men, addressed the subject of whiskey in their novels. Although Prohibition played a role for all three, each brought a different context and perspective to the subject, as will be evident below.

During more than four decades of literary work, Ellen Glasgow (1873-1945) published twenty novels, a collection of poems, a book of short stories, and a book of literary criticism. Although in her lifetime Glasgow won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction, her works, somewhat undeservingly, are little read today. A native of Richmond, Virginia, where she lived for most of her life, much of her work centered around life in the Commonwealth. This is particularly true of a novel she published in 1926 called “The Romantic Comedians.”

During more than four decades of literary work, Ellen Glasgow (1873-1945) published twenty novels, a collection of poems, a book of short stories, and a book of literary criticism. Although in her lifetime Glasgow won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction, her works, somewhat undeservingly, are little read today. A native of Richmond, Virginia, where she lived for most of her life, much of her work centered around life in the Commonwealth. This is particularly true of a novel she published in 1926 called “The Romantic Comedians.”

The whiskey Glasgow cited was not fictional. On land that their family had owned and occupied almost since the American Revolution, James Baumgardner put the family name in the forefront of American distillers and established Virginia-made whiskey nationally as a quality liquor. When the Civil War ended, Baumgardner’s farm and distillery were in ruins, many of his slaves had departed and the entire countryside lay in ruins. Undeterred, he determined to recoup his fortunes by expanding a small distillery and making "Bumgardner Pure Old Rye Whiskey" a well-known, respected brand. His bottles bore labels that depicted an artist's view of his operation. James' motto for his whiskey was: Wherever it goes, it goes to stay." Before long Bumgardner's whiskey was being sold from coast to coast.

The whiskey Glasgow cited was not fictional. On land that their family had owned and occupied almost since the American Revolution, James Baumgardner put the family name in the forefront of American distillers and established Virginia-made whiskey nationally as a quality liquor. When the Civil War ended, Baumgardner’s farm and distillery were in ruins, many of his slaves had departed and the entire countryside lay in ruins. Undeterred, he determined to recoup his fortunes by expanding a small distillery and making "Bumgardner Pure Old Rye Whiskey" a well-known, respected brand. His bottles bore labels that depicted an artist's view of his operation. James' motto for his whiskey was: Wherever it goes, it goes to stay." Before long Bumgardner's whiskey was being sold from coast to coast.

Writing six years after National Prohibition was imposed, Glasgow describes its effects on her fictional Judge Honeywell. The Judge no longer enjoys going to his club now that no alcohol was being served. He jealously guards his dwindling supplies of Old Baumgardner and carefully monitors other family members who may want to sample some. The author, however, is silent on the subject of Prohibition itself. As a final note, Baumgardner Whiskey was not revived after Repeal.

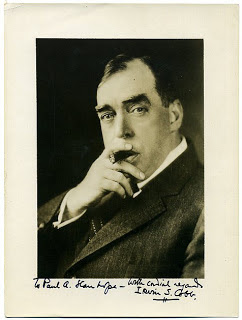

Glasgow’s silence is in distinct contrast to the stance of Irvin J. Cobb (1876-1944), once among America’s top celebrities: Author of sixty books , a writer once compared favorably with Mark Twain, Cobb was the country’s highest paid journalist; a star of radio, motion pictures, and the lecture circuit. He hosted the Academy Awards in 1935, received the French Legion of Honor and awarded two honorary doctorates. Initially Cobb saw Prohibition as a subject for humor.

Glasgow’s silence is in distinct contrast to the stance of Irvin J. Cobb (1876-1944), once among America’s top celebrities: Author of sixty books , a writer once compared favorably with Mark Twain, Cobb was the country’s highest paid journalist; a star of radio, motion pictures, and the lecture circuit. He hosted the Academy Awards in 1935, received the French Legion of Honor and awarded two honorary doctorates. Initially Cobb saw Prohibition as a subject for humor.

That jocular attitude had vanished by 1929 when Cobb wrote the only American novel devoted to the whiskey industry. Called “Red Likker,” his book tells the story of an old Kentucky family who founded a distillery called “Bird and Son” in the wake of the Civil War. It traces the history of this enterprise up to the time of Prohibition when it is forced to close. Ultimately the distillery is destroyed by fire and the family is reduced to running a crossroads grocery store.

That jocular attitude had vanished by 1929 when Cobb wrote the only American novel devoted to the whiskey industry. Called “Red Likker,” his book tells the story of an old Kentucky family who founded a distillery called “Bird and Son” in the wake of the Civil War. It traces the history of this enterprise up to the time of Prohibition when it is forced to close. Ultimately the distillery is destroyed by fire and the family is reduced to running a crossroads grocery store.

Central to the novel is Cobb’s polemic against Prohibition. Colonel Bird, the fictional founder of the distillery, argues at great length with his sister, Juanita, a teetotaler and Prohibitionist, about the pros and cons of permitting the sale of alcoholic beverages. The Colonel ultimately triumphs: When the Volstead Act reduces the 42% alcohol in Juanita’s patent medicine, she is shown to be an alcoholic. She revives only when the Colonel pours her a shot of Kentucky bourbon.

Not only did Cobb inveigh against Prohibition in his literary works, he also made it a personal crusade. He became chairman of the Authors and Artists Committee of the Association Against the Prohibition Amendment. Under his vigorous leadership, the committee ultimately boasted 361 members including some of the leading figures of the day. As chairman, he released statements to the press blaming Prohibition for increased crime, alcoholism and disrespect for the law. “If Prohibition is a noble experiment,” he said in one, “then the San Francisco fire and the Galveston flood should be listed among the noble experiments of our national history.” With the law’s repeal in 1934, Cobb authored a pamphlet of cocktail recipes.

Not only did Cobb inveigh against Prohibition in his literary works, he also made it a personal crusade. He became chairman of the Authors and Artists Committee of the Association Against the Prohibition Amendment. Under his vigorous leadership, the committee ultimately boasted 361 members including some of the leading figures of the day. As chairman, he released statements to the press blaming Prohibition for increased crime, alcoholism and disrespect for the law. “If Prohibition is a noble experiment,” he said in one, “then the San Francisco fire and the Galveston flood should be listed among the noble experiments of our national history.” With the law’s repeal in 1934, Cobb authored a pamphlet of cocktail recipes.

Sherwood Anderson (1876-1941), an established figure as a major American author, devoted a 1936 novel to yet another aspect of the Prohibition era — bootleg alcohol. Although not an activist like Cobb, in 1927 Anderson wrote an article entitled “Prohibition” for Vanity Fair magazine. There he stated: Well enough I know that my voice is a feeble one. What I say will have no effect. However I feel this inclination to speak up. It has seemed to me, from the very beginning, that this whole matter of prohibition has been put on the wrong footing. We should begin to find out, sometime, that people are not changed by laws. You do not make men moral or immoral that way….Prohibition—the triumph of vulgarity. That is all I can see in the matter.

Sherwood Anderson (1876-1941), an established figure as a major American author, devoted a 1936 novel to yet another aspect of the Prohibition era — bootleg alcohol. Although not an activist like Cobb, in 1927 Anderson wrote an article entitled “Prohibition” for Vanity Fair magazine. There he stated: Well enough I know that my voice is a feeble one. What I say will have no effect. However I feel this inclination to speak up. It has seemed to me, from the very beginning, that this whole matter of prohibition has been put on the wrong footing. We should begin to find out, sometime, that people are not changed by laws. You do not make men moral or immoral that way….Prohibition—the triumph of vulgarity. That is all I can see in the matter.

An Anderson’s novel, “Kit Brandon,” tells the rambling tale of its title heroine, a woman from the mountains of Appalachian Virginia who is heavily involved in illegally making and selling whiskey. The author knew that region well, having lived there for almost 30 years. A major character, Tom Halsey, has been distilling moonshine whiskey. After Prohibition is imposed Halsey decides to enlarge his operation: “He had got his neighbors who were liquor makers…there were enough of them, all small makers, little groups of men going in together…He had got them all to bring the stuff to him.” Kit becomes a principal driver for Halsey, guiding other cars full of illegal whiskey across the mountains.

An Anderson’s novel, “Kit Brandon,” tells the rambling tale of its title heroine, a woman from the mountains of Appalachian Virginia who is heavily involved in illegally making and selling whiskey. The author knew that region well, having lived there for almost 30 years. A major character, Tom Halsey, has been distilling moonshine whiskey. After Prohibition is imposed Halsey decides to enlarge his operation: “He had got his neighbors who were liquor makers…there were enough of them, all small makers, little groups of men going in together…He had got them all to bring the stuff to him.” Kit becomes a principal driver for Halsey, guiding other cars full of illegal whiskey across the mountains.

In the novel Anderson views Prohibition as a move of “haves” against “have nots": “‘Oh , pride, oh cocksureness. The saloon must never come back.’ Now it will become fashionable, a real mark of distinction, to have a stock of liquor in the home.’We the rich and well-to-do, can have it now. The others, of the lower classes the workers, they cannot get it. ’You’ll see they will be better workers now.’” Anderson also relates the story of a hypocritical prohibition-supporting U.S. Senator drinking from a bottle marked as medicine that he keeps refilled with corn whiskey brought by constituents.

Although each of these authors addressed Prohibition from a different perspective, they illuminated a few of the multiple impacts the ban on alcohol had on American life and society. All three, I suspect, celebrated Repeal.

No comments:

Post a Comment