Noting that a prior post on risqué whiskey advertising has proved popular (May 25, 2023) I am emboldened to present a second post that presents the kind of “naughty” pictures meant to entice pre-Prohibition men to purchase a specific brand of whiskey. As the title here suggests, such images were produced all over America.

Dreyfus & Weil, Paducah, Kentucky, distillers provided a somewhat more suggestive trade card of young women, in this case dancers, raising up their skirts while three bonafide “dirty old men” take a long look. Sam H. Dreyfuss and his partner regularly were excoriated in the press for the sexual images they presented in their merchandising. Their “Devil’s Island Endurance Gin,” sold with suggestive advertising was accused by critics of having been instrumental in rapes and even one murder.

From lifted skirts to bared bosoms, we head west to San Francisco where Roth & Company had trademarked “Capitol O.K. Whiskey” in 1906. Its saloon sign depicted an underwater topless beauty. Joseph Roth founded this firm in 1859, initially located in the old U.S. Courthouse near Oregon Street. After working with several partners over the years, Roth died in 1891 and the firm in 1906 was bought by Edwin Scheeling and his wife. The earthquake and fire that year destroyed the premises but the Scheelings rebuilt and the business survived until the arrival of National Prohibition.

From lifted skirts to bared bosoms, we head west to San Francisco where Roth & Company had trademarked “Capitol O.K. Whiskey” in 1906. Its saloon sign depicted an underwater topless beauty. Joseph Roth founded this firm in 1859, initially located in the old U.S. Courthouse near Oregon Street. After working with several partners over the years, Roth died in 1891 and the firm in 1906 was bought by Edwin Scheeling and his wife. The earthquake and fire that year destroyed the premises but the Scheelings rebuilt and the business survived until the arrival of National Prohibition.

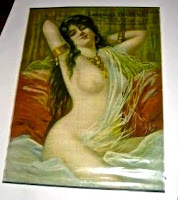

Other popular advertising gimmicks were calendars. They might be hung up in a drinking establishment or more cautiously in a customer’s “man cave.” This beauty graced a calendar issued by the Brolinski Saloon of Niagara Falls, New York, likely given out to the boys along the bar. Brolinski likely bought this image from a catalogue and personalized it by having his name and address attached. The lady involved was clearly a Middle Eastern harem dweller, a popular exotic image of the pre-Pro era.

Other popular advertising gimmicks were calendars. They might be hung up in a drinking establishment or more cautiously in a customer’s “man cave.” This beauty graced a calendar issued by the Brolinski Saloon of Niagara Falls, New York, likely given out to the boys along the bar. Brolinski likely bought this image from a catalogue and personalized it by having his name and address attached. The lady involved was clearly a Middle Eastern harem dweller, a popular exotic image of the pre-Pro era.

Also popular were representations of Greek goddesses in various states of undress. They are found on a number of whiskey advertising items, including signs, trade cards, celluloid pocket mirrors and, as in this case, paperweights. The weight above shows Diana, the goddess of the hunt, in a forest setting with her bow in hand and half-clothed in something filmy. She has just fired an arrow, likely into a deer offstage. The item was issued by the Fleischmann Company, famous for yeast, but also a major producer of whiskey under a number of brand names.

Another lass clothed only in gauze is somewhat inexplicably holding onto a horse in this trade card. She may, however, be what one Milwaukee liquor dealer thought Lady Godiva might look like. He was A. M. Bloch who founded his enterprise in 1877. Over the thirty years of its existence Bloch’s firm was located at several addresses on the city’s Water Street, where many of its liquor emporiums were located. Although not mentioned on this ad, Bloch’s flagship brand was “Joker Club.”

Another lass clothed only in gauze is somewhat inexplicably holding onto a horse in this trade card. She may, however, be what one Milwaukee liquor dealer thought Lady Godiva might look like. He was A. M. Bloch who founded his enterprise in 1877. Over the thirty years of its existence Bloch’s firm was located at several addresses on the city’s Water Street, where many of its liquor emporiums were located. Although not mentioned on this ad, Bloch’s flagship brand was “Joker Club.”

Even staid Boston could spawn a risqué image, this one from Felton & Son, founded by F. L. Felton and located in South Boston. The company house brands were “Felton Rye,” “Old Felton Rye,” and “Felton’s New England Rum,” the latter the excuse for this tantalizing saloon reverse glass sign. The Feltons were distillers and known most particularly for their rum, advertised as“…Unsurpassed by any in the market, is warranted copper distilled, perfectly pure….” Would the Feltons, I wonder, have vouched for the “perfect purity” of the nude on their sign?

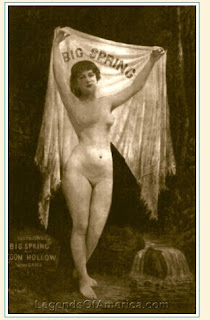

At this point, all modesty has flown away. Whatever covering this nude may have had is now held above her head, advertising “Big Spring” whiskey. This sweetie was brought to the public by the infamous “Whiskey Trust,” an attempt to create a monopoly in the whiskey trade in order to drive up prices. Located in Louisville, the organization officially was known as the Kentucky Distilleries & Warehouse Company. More successful than other similar attempts at combining distilleries the Kentucky outfit operated from 1902 to 1919, buying or spawning more than a dozen brands, but it never achieved its profit goals.

The invention of celluloid made possible a variety of liquor-related advertising items that retain their appeal even a century or more later. The shapely female shown on this match safe is a excellent example of celluloid art, even though it is difficult to understand why light is shining from the palms of her hands. This interesting image was brought to the drinking public by Herman Frech, a pre-Prohibition Minneapolis liquor dealer, located at 14-16 North Sixth Street. His logo, unseen here, appears on the opposite side. It presents his name, a whiskey bottle, two glasses and a box of cigars.

The invention of celluloid made possible a variety of liquor-related advertising items that retain their appeal even a century or more later. The shapely female shown on this match safe is a excellent example of celluloid art, even though it is difficult to understand why light is shining from the palms of her hands. This interesting image was brought to the drinking public by Herman Frech, a pre-Prohibition Minneapolis liquor dealer, located at 14-16 North Sixth Street. His logo, unseen here, appears on the opposite side. It presents his name, a whiskey bottle, two glasses and a box of cigars.

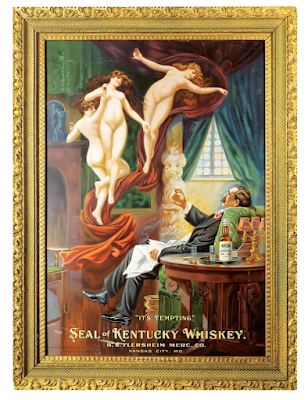

If one nude sells whiskey, hey — why not try three? That may have motivated B.S. Flersheim to issue a trio of nudes on a saloon sign advertising his mercantile company in Kansas City, Missouri. The sign, that sold in 2019 for $37,000, displays the unclad ladies visiting a gent sitting in an easy chair and quaffing a brand of whisky aptly named, “Its Tempting.” That label was trademarked in 1904. Another B.S. Flersheim & Company brand was “Old Bondage.” Its use on this sign would have been really kinky. Founded in 1879, Flersheim’ liquor business survived until 1918, a 37 year run.

There they are risqué whiskey fans. A dozen females in various stages of dress and undress. They were issued all over the country, from reputedly stogy places like Boston and Milwaukee to more exciting locales like San Francisco and Niagara Falls. These images all had the same purpose: to sell whiskey. Moreover, they all faced the same fate: Banishment to the ranks of collectibles once women begin to frequent drinking establishments.

Note: Longer vignettes on two of the “whiskey men” noted in this post are to be found elsewhere on this website: David Sachs, October 25, 2011, and Dreyfuss & Weil, March 1, 2013.

.jpg-%20L.jpg)

.jpg-%20C.jpg)