Coming from a prominent Pennsylvania distilling family, members of the Rohrer clan about 1837 migrated across state lines to settle in Germantown, Ohio. There two generations of Rohrers continued making liquor. Their Mud Lick Distillery would become among the most famous in America, highly successful until the Great Flood of 1913 bankrupted the company and prohibitionary laws made it impossible to recover. The story is best told through three family members — Christian, David, and John Rohrer — who together guided the family distilling destiny for 76 years.

Early Rohrer History: The Rohrer clan were among the earlier settlers of Pennsylvania, deeded land in Lancaster County by an agent of William Penn. There in December,1804, Christian Rohrer was born on the farm where his father and grandfather, also named Christian, had been born. As Unitarians the Rohrers had no prejudice against alcohol and distilling was part of their agricultural production. (See post on Jeremiah Rohrer, Oct. 16, 2015.)

Christian Rohrer: Shown here in later life, Christian is said to have received a good education and upon achieving his majority inherited from his father’s estate a farm and sawmill. Restless nonetheless, in 1931 he ventured into Ohio to assess that territory and was impressed with prospects in German Township of Montgomery County. Christian came home, sold his farm, and headed to Ohio.

Christian Rohrer: Shown here in later life, Christian is said to have received a good education and upon achieving his majority inherited from his father’s estate a farm and sawmill. Restless nonetheless, in 1931 he ventured into Ohio to assess that territory and was impressed with prospects in German Township of Montgomery County. Christian came home, sold his farm, and headed to Ohio.

Christian’s move there may have been motivated, at least in part, by a romantic attraction. In Germantown he met Margaret Emerick, the locally born daughter of Christopher and Catherine Kern Emerick, a couple who had settled there in 1804. Shown here in maturity, Margaret married Christian in November 1832. Over ensuing years the couple would have five children, three girls and two boys.

Christian’s move there may have been motivated, at least in part, by a romantic attraction. In Germantown he met Margaret Emerick, the locally born daughter of Christopher and Catherine Kern Emerick, a couple who had settled there in 1804. Shown here in maturity, Margaret married Christian in November 1832. Over ensuing years the couple would have five children, three girls and two boys.

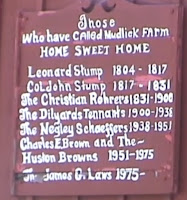

Christian’s first move was to buy an existing flour mill that he operated for several years. He then purchased the mill of Col. John Stump, located on 75 acres of land. Still standing, the mill building, dated 1817, bears a plaque that credits the Rohrers with ownership from 1831 to 1900. The mill was located adjacent to Mudlick Creek that provided water for whiskey and power to mash grain. The property contained an idle distillery, shown below, that Christian refurbished and expanded.

He then began distilling liquor that soon achieved a reputation for quality far beyond its origins. What made Mud Lick Whiskey so good was the mineral rich waters of the springs that fed Mudlick Creek. Throughout the 1900s those presumably healing waters had drawn believers from all over America. Many now went home with a bottle of what has been called “the soothing whiskey” from the Rohrer distillery. This small facility, however, had limitations, capable of producing less than ten barrels of liquor a day.

Christian became known as “one of the solid and successful businessmen” of the mid-Ohio region. In addition to expanding the distillery as shown below, he co-founded the First National Bank of Germantown, still in business today, and was an early investor in the Cincinnati, Hamilton & Dayton Railway, an electric inter-urban line. A biographer said of Christian: “(He) always took a deep interest in worthy public enterprises, as well as in the progress, growth and development of the valley.”

As he aged, Christian retired from management of the Mud Lick Distillery, turning over the work to his son, David. The father, age 78, died in July 1883 and was buried in the Gemantown Cemetery. A large monument was erected by his family over Christian’s grave.

As he aged, Christian retired from management of the Mud Lick Distillery, turning over the work to his son, David. The father, age 78, died in July 1883 and was buried in the Gemantown Cemetery. A large monument was erected by his family over Christian’s grave.

David Rohrer: As Christian’s eldest son, David, shown here, was the heir apparent. Born in November 1835, he was educated in the Germantown public schools and at age 22 entered his father’s distillery, quickly being made a partner. The company became C.Rohrer & Son. After succeeding to the company presidency in 1861, David embarked on an expansion program that increased distillery capacity considerably, as indicated in the painting below.

David Rohrer: As Christian’s eldest son, David, shown here, was the heir apparent. Born in November 1835, he was educated in the Germantown public schools and at age 22 entered his father’s distillery, quickly being made a partner. The company became C.Rohrer & Son. After succeeding to the company presidency in 1861, David embarked on an expansion program that increased distillery capacity considerably, as indicated in the painting below.

The distillery proved to be a boon to Germantown. At its height the Mud Lick plant employed 30 workmen who turned out 40 barrels of the bourbon daily. That production fattened 400 head of cattle and 1200 hogs annually with the spent whiskey mash. About 20,000 barrels were kept aging at one time at Mud Lick, representing a $1 million inventory.

In 1868 Charles Hofer, a liquor dealer of Cincinnati, was admitted as a partner. This partnership existed until 1883, when David purchased Hofer's interest and took full control of the Mud Lick Distillery. He renamed it “D. Rohrer & Co.” During ensuing years he appeared to be a marked success at guiding one of the Nation’s largest distilleries. David also became an extensive landowner, purchasing 800 acres of farmland in the vicinity of Germantown and 3,000 acres in newly opened Indian lands in North Dakota. His fortune, calculated in todays dollar, would exceed $8 million.

In 1868 Charles Hofer, a liquor dealer of Cincinnati, was admitted as a partner. This partnership existed until 1883, when David purchased Hofer's interest and took full control of the Mud Lick Distillery. He renamed it “D. Rohrer & Co.” During ensuing years he appeared to be a marked success at guiding one of the Nation’s largest distilleries. David also became an extensive landowner, purchasing 800 acres of farmland in the vicinity of Germantown and 3,000 acres in newly opened Indian lands in North Dakota. His fortune, calculated in todays dollar, would exceed $8 million.

Buoyed by his wealth, David decided to build his family and himself a mansion home like none Germantown had seen before. In February 1865 David had married Ada V. Rohrer, shown here. Ada was a distant cousin whose parents Samuel and Elizabeth Schultz Rohrer, originally natives of Maryland, had joined the Rohrer clan in Germantown in 1926. Over the next few years the couple would have five children, three girls and two boys.

Buoyed by his wealth, David decided to build his family and himself a mansion home like none Germantown had seen before. In February 1865 David had married Ada V. Rohrer, shown here. Ada was a distant cousin whose parents Samuel and Elizabeth Schultz Rohrer, originally natives of Maryland, had joined the Rohrer clan in Germantown in 1926. Over the next few years the couple would have five children, three girls and two boys.

Still standing at 1201 West Market Street’, the house is a three-story, 15-room brick mansion The six-course walls were built with bricks fired on the Rohrer Farm. The woodwork was cut directly from a stand of hardwood timber on the property. While continuing to be a private residence, the Rohrer House currently also is available for tours.

The mansion seemed to cap a highly successful career for David. He was hailed in the 1897 Centennial Portrait and Biographical Record of the City of Dayton and of Montgomery County, Ohio. this way: Mr. Rohrer is one of the progressive business men of Montgomery County, whose success has been achieved by upright dealing in all the affairs of life.”

The Fall of the House of Rohrer: Things were not as they seemed for David and the Rohrers. As the early years of the 20th Century passed, sales of Mud Lick Whiskey slumped as competitive brands appeared and prohibitionary forces increasingly closed off markets. Additionally, David found himself over-extended financially with liabilities of $200,000 (1910 dollars) while claiming assets of $300,000.

The Fall of the House of Rohrer: Things were not as they seemed for David and the Rohrers. As the early years of the 20th Century passed, sales of Mud Lick Whiskey slumped as competitive brands appeared and prohibitionary forces increasingly closed off markets. Additionally, David found himself over-extended financially with liabilities of $200,000 (1910 dollars) while claiming assets of $300,000.

Taken to court by creditors said to be owed $30,000, David in a legal maneuver, in November 1909 signed a “deed of assignment” to the Mud Lick distillery and other properties to a former judge, Charles Dale, and his brother, John. He told the press he had taken the action believing that “the creditors will not lose a dollar and that the action would result in conserving his property.”

John Rohrer, a younger brother, had a sterling reputation in Germantown as a businessman. After a four year gambit in the West speculating in real estate and cattle, he had returned home to found a tobacco brokerage and later a grain, coal and lumber company. His and Dale’s participation in this assignment of Rohrer assets was viewed sympathetically by the local press. Noting David’s 50 years in local business, one story commented that the move was made “to prevent a sacrifice” of Rohrer property.

|

| Edward Patterson |

Behind the assignment, however, was a story that suggested criminality. In subsequent bankruptcy proceedings, Edward Patterson, a distiller and whiskey broker from Cincinnati charged that David had committed fraud. (See post on Patterson, Jan.28, 2021.) Shown here, Patterson told a bankruptcy court in November 1909 that David had pledged 800 barrels of Mud Lick whiskey aging in Rohrer warehouses as security for large loans Patterson had made to him. He testified that all but 210 of those barrels subsequently had been sold to other buyers without his knowledge or approval. He laid claim to the remaining barrels as partial compensation. Multiple commitment of the same warehoused whiskey was a frequent ploy in the distilling trade — and a crime.

In bankruptcy proceedings beginning in November 1909, the claims of multiple petitioners, including Patterson, apparently were settled without charges being brought against David, by now in his mid-seventies. My surmise is that John Rohrer was responsible for surviving the bankruptcy, satisfying the creditors, and quashing any further legal action.

Able to retain the distillery, the Rohrers’ production of Mud Lick Whiskey limped along for the next several years. That came to an end with the great Midwestern floods of March 1913 that claimed 640 victims, most of them in Ohio. Still considered the state’s largest weather disaster, the water sent the Miami River rampaging through Germantown, destroying much of the distillery. The remaining buildings went up in flames as ruptured gas lines ignited.

Given the circumstances, the Rohrers decided not to rebuild their distillery and are said to have taken the much coveted recipe for Mud Lick whiskey with them to the grave. For David Rohrer that was in 1917, only four years after the flood. He was buried in the Germantown Cemetery adjacent to Christian. His gravestone is shown here. Ada would be buried beside him in 1920.

Given the circumstances, the Rohrers decided not to rebuild their distillery and are said to have taken the much coveted recipe for Mud Lick whiskey with them to the grave. For David Rohrer that was in 1917, only four years after the flood. He was buried in the Germantown Cemetery adjacent to Christian. His gravestone is shown here. Ada would be buried beside him in 1920.

Notes: This post has been gathered from a variety of Internet sources. Key among them were “Centennial Portrait and Biographical Record of the City of Dayton and of Montgomery County, Ohio — 1897” and court documents. The two photos here of David Rohrer came to light not long ago, found for sale in a Springfield Ohio flea market.

No comments:

Post a Comment