A Scottish immigrant, David Porter began his California career as a drayman, driving a team of horses hauling barrels for a liquor dealer. Before long Porter owned the company and had expanded his business interests and wealth to become part of the city’s financial elite and make his daughter the object of greedy eyes. Then came an event that changed everything.

Born in Scotland in 1833, Porter arrived in the Golden State in 1845 at the age of 18. He likely had been raised on a farm, exhibiting a knowledge of livestock. He soon secured work with the liquor house of Fox & Connor in Stockton, California driving a horse-powered wagon around the city. According to one observer, Porter demonstrated “so much zeal and capacity” that the partners soon advanced him to bookkeeper.

In 1854 when the company moved 83 miles west to San Francisco, the Scotsman had become so valuable a part of the operation, he was made a partner. Not long after the move Connor left the business and the firm of Fox & Porter was born, doing its liquor sales at the corner of Leidesdorff and Clay Streets in San Francisco’s financial district.

After some 14 years working successfully as partners, Henry Fox retired and Porter purchased his interest. With the company name now simply “David Porter,” the sole proprietor moved to the Parrott Building, shown here, at the northwest corner of Montgomery and California Streets, considered a premier location. There Porter wasted no time asserting his merchandising genius, rapidly building his wholesale liquor house into among San Francisco’s largest.

After some 14 years working successfully as partners, Henry Fox retired and Porter purchased his interest. With the company name now simply “David Porter,” the sole proprietor moved to the Parrott Building, shown here, at the northwest corner of Montgomery and California Streets, considered a premier location. There Porter wasted no time asserting his merchandising genius, rapidly building his wholesale liquor house into among San Francisco’s largest. Porter’s flagship brand was Shield Bourbon Whiskey, a name he never bothered to trademark. He made no pretense about being a distiller, announcing on rather that the whiskey had been distilled “expressly” for him. The source remains unknown although Kentucky might be expected given his use of the term bourbon.

Porter’s flagship brand was Shield Bourbon Whiskey, a name he never bothered to trademark. He made no pretense about being a distiller, announcing on rather that the whiskey had been distilled “expressly” for him. The source remains unknown although Kentucky might be expected given his use of the term bourbon.  He packaged his product in ceramic jugs with a with an elaborate label that contained a simulated coat of arms depicting a plumed knight and the initials “D.P.” (David Porter) and “S.F.” (San Francisco). Those jugs, as shown here, came in sizes ranging from a quart to a half gallon.

He packaged his product in ceramic jugs with a with an elaborate label that contained a simulated coat of arms depicting a plumed knight and the initials “D.P.” (David Porter) and “S.F.” (San Francisco). Those jugs, as shown here, came in sizes ranging from a quart to a half gallon. Meanwhile, Porter was rising in San Francisco business circles. Accounted a millionaire in the press, he was hobnobbing with the city’s elite. For example, when local luminaries such as Leland Stanford, founder of Stanford University, and railroad executives and bankers, Charles Crocker and Mark Hopkins, decided to choose California Street as a residence location for themselves, a franchise was granted to a group for a cable railroad that included the “Big Three,” with David Porter and others. The line was soon constructed. Shown here at its terminal and power house, the cable car stretched from First Street to Kearney, serving the mansion homes on the hilltop.

Meanwhile, Porter was rising in San Francisco business circles. Accounted a millionaire in the press, he was hobnobbing with the city’s elite. For example, when local luminaries such as Leland Stanford, founder of Stanford University, and railroad executives and bankers, Charles Crocker and Mark Hopkins, decided to choose California Street as a residence location for themselves, a franchise was granted to a group for a cable railroad that included the “Big Three,” with David Porter and others. The line was soon constructed. Shown here at its terminal and power house, the cable car stretched from First Street to Kearney, serving the mansion homes on the hilltop.

Among them was the Porter mansion at 1414 Folsom Street that had a commanding view of San Francisco from atop Nob Hill. Now the site of the posh Fairmont Hotel, the liquor baron’s home was two and a half stories high with a wrap-around yard and garden. Of frame construction, it was Victorian in architecture — a visible sign of wealth and wellbeing. The net worth Porter gave the 1870 census taker was equivalent to over $1,000,000 today.

As he advanced, Porter never forgot his Scottish roots. He was a ruling elder and large contributor to St. John Presbyterian Church, organized in 1870 with 220 members, and he assisted with the purchase of a place of worship. He also was the president of the local St. Andrew’s Society, formed for the purpose of granting temporary relief to impoverished Scotsmen and their families. Again, he was generous in his philanthropy.

Sharing the mansion with David was his wife, the former Elizabeth Green, who had been born in Maryland of immigrant Irish parents. She was eleven years younger than her husband. They had married in the late 1860s and had two children, Grace born in 1868 and Mary in 1870. The 1870 census found the family living in the Folsom Street mansion with Elizabeth’s mother, Mary Green, and a man identified as a bookkeeper, likely working for Porter in his liquor house.

As his reputation as a businessman rose, Porter and his wife became known a socialites, entertaining frequently in their mansion home. In 1884 they hosted an opera singer named Enrico Campobello, a dashing figure who had made a splash in San Francisco society. One of a number of British singers of the time who adopted Italian identities, Campobello’s real name was Henry Mclean Martin, born in Campbeltown, Scotland.

As his reputation as a businessman rose, Porter and his wife became known a socialites, entertaining frequently in their mansion home. In 1884 they hosted an opera singer named Enrico Campobello, a dashing figure who had made a splash in San Francisco society. One of a number of British singers of the time who adopted Italian identities, Campobello’s real name was Henry Mclean Martin, born in Campbeltown, Scotland.

The Porters likely were thrilled to have a celebrity like Martin who reputedly came with letters of introduction from acquaintances of David’s in Scotland. One can imagine the two men having a pleasant evening recounting their memories of the old country. Campobello/Martin was married and sang with his wife, an operatic soprano. When their tour ended, the baritone/bass announced that he would stay in Frisco and form his own opera company. His wife left town without him.

Little did the Porters realize what was transpiring. At their home Compobello/Martin had met their daughter, Grace, now a winsome young woman of 16, and decided that marriage to an heiress would assure his future. The inexperienced Grace for her part was utterly smitten with the suave opera singer. The unsuspecting Porters even hosted the fortune-seeker the following year. When David finally understood what his fellow Scotsman was up to, he forbade him to visit the mansion ever again. But it was too late. Campobello/Martin divorced his wife and induced the love-smitten teenager to run away with him and marry.

As one writer commented: “San Francisco society was shocked. It was all very well to have singing lessons from the handsome baritone, but to marry him….Back in England, the St. James Hotel in Piccadilly advertised they were selling off a trunk of his property…that he’d abandoned there. But Henry didn’t care. He’d married a millionaire’s daughter.” How David Porter and his wife reacted to the marriage is unclear. The marriage itself may have been shortlived. A San Francisco newspaper in Jun 1893 reported: “Mrs. Grace Porter Campobello is visiting her parents, Mr. and Mrs. David Porter, on California street, and will not probably rejoin her husband in Memphis.”

For onlookers, Porter appeared to continue to operate a successful liquor house as before and manage a portfolio of other investments. As one press account called him “one of the most widely known of San Francisco merchants.” He made a business call in the late afternoon of January 17,1893, arriving at the Mills Building, a major financial center shown here, and took the elevator to the seventh floor. After visiting an office there, the liquor dealer returned to the elevator that stood next to a spiral staircase open to the ground floor lobby.

For onlookers, Porter appeared to continue to operate a successful liquor house as before and manage a portfolio of other investments. As one press account called him “one of the most widely known of San Francisco merchants.” He made a business call in the late afternoon of January 17,1893, arriving at the Mills Building, a major financial center shown here, and took the elevator to the seventh floor. After visiting an office there, the liquor dealer returned to the elevator that stood next to a spiral staircase open to the ground floor lobby. Suddenly Porter fell. He crashed on the second floor, fracturing his skull, and died instantly as his body rolled down the stairs to the lobby. A coroner’s jury ruled it an accidental death. The San Francisco Examiner the following day report that the liquor dealer had been ill and the previous Sunday had suffered a bout of vertigo. Its story speculated that when an elevator car was not at hand, Porter walked over to the bannister, looked down the seven stories, had a second attack of vertigo, tipped over the railing and plunged fifty feet to the second floor. The newspaper termed it: “A fearful descent.”

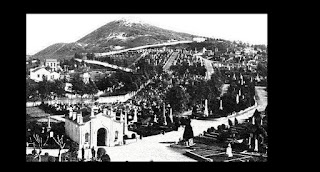

Suddenly Porter fell. He crashed on the second floor, fracturing his skull, and died instantly as his body rolled down the stairs to the lobby. A coroner’s jury ruled it an accidental death. The San Francisco Examiner the following day report that the liquor dealer had been ill and the previous Sunday had suffered a bout of vertigo. Its story speculated that when an elevator car was not at hand, Porter walked over to the bannister, looked down the seven stories, had a second attack of vertigo, tipped over the railing and plunged fifty feet to the second floor. The newspaper termed it: “A fearful descent.” After an inquest, Porter’s body was taken from the San Francisco Morgue to Wright’s undertaking establishment where it was prepared for a well attended funeral at St. John Presbyterian Church. He initially was buried at San Francisco’s historic Laurel Hill Cemetery, shown here in a vintage photo. In 1901 the city, in order to make more space for development, ordered all graves within the city limits to be moved elsewhere. Some 35,000 buried at Laurel Hill were forced out of San Francisco and moved to a former Japanese cemetery in the adjoining community of Colma, the graveyard now called Cypress Lawn. Porter’s body was among those re-buried but without any identifying monument or headstone.

After an inquest, Porter’s body was taken from the San Francisco Morgue to Wright’s undertaking establishment where it was prepared for a well attended funeral at St. John Presbyterian Church. He initially was buried at San Francisco’s historic Laurel Hill Cemetery, shown here in a vintage photo. In 1901 the city, in order to make more space for development, ordered all graves within the city limits to be moved elsewhere. Some 35,000 buried at Laurel Hill were forced out of San Francisco and moved to a former Japanese cemetery in the adjoining community of Colma, the graveyard now called Cypress Lawn. Porter’s body was among those re-buried but without any identifying monument or headstone.

Not long after Porter’s death speculation arose that his fall might not have been accidental. Although all his obituaries spoke of his wealth, Porter soon was revealed no longer to be a rich man. He apparently owed large amounts of money and was on the brink of bankruptcy. Could the fall be attributed to financial distress? The individual most shocked by this news may have been Campobello/Martin. Despite appearances, his wife’s father was actually no millionaire after all. Porter had died worse than penniless, it seemed, and Grace had nothing to inherit. Additionally, after his death the liquor house that Porter had built over almost a half century went out of business.

David Porter, however, deserves to be remembered by something better than the manner of his death. He was, after all, a Scottish immigrant who rose from a lowly drayman to owning a major liquor house and respect as one of San Francisco’s premier pioneer merchants.

How nice to be quoted! Even anonymously... did you read my VICTORIAN VOCALISTS or my blog? We are still searching for Campo's grave/death in San Diego (?). Excellent article. Grace was of course 21 when she wed Archie. Best wishes, Kurt Gänzl.

ReplyDeleteMr. Kurt Ganzel: I appreciate your kind remarks about my article on David Porter. I have checked my notes for the article and do not know where I saw the quote from Victorian Vocalists. Basically drew the information from items in the San Francisco newspapers that were in the public domain. Since my story was about David Porter and not Campo did not worry about Henry's place of interment. I am delighted to identify you here as the author of the excellent quote on Henry Campo above. Nicely crafted.

ReplyDelete