The rise of Mathias J. “Matt” Hinkel, shown here, from twelve-year-old office boy in Cleveland to nationally known millionaire sportsman, boxing promoter and prize fight referee was a phenomenon founded on the sale of alcohol. From 1892 to 1919, Hinkel’s prosperous wholesale trade in wines and “jobber of fine whiskey” made possible his forays into boxing, baseball, and horse racing as well as financing the establishment of other Cleveland businesses.

Born in the Ohio city in 1867, Hinkel was the son of Catherine (Sauer) and Jacob Hinkel, both immigrants from Hesse Darmstadt, Germany. Although Jacob’s occupation in the 1880 census was given as “merchant,” he may not have been a successful one. Matt was forced to quit school at 12 years old and go to work as an office boy for Edwards, Townsend & Company, a major Cleveland wholesale grocery and liquor emporium. According to a biographer, “…By close attention to business and faithfulness and diligence [Hinkel] rose to the position of manager of their liquor department.” Because Edwards, Townsend relied heavily on liquor sales, Hinkel became a key company executive while still in his teens.

Born in the Ohio city in 1867, Hinkel was the son of Catherine (Sauer) and Jacob Hinkel, both immigrants from Hesse Darmstadt, Germany. Although Jacob’s occupation in the 1880 census was given as “merchant,” he may not have been a successful one. Matt was forced to quit school at 12 years old and go to work as an office boy for Edwards, Townsend & Company, a major Cleveland wholesale grocery and liquor emporium. According to a biographer, “…By close attention to business and faithfulness and diligence [Hinkel] rose to the position of manager of their liquor department.” Because Edwards, Townsend relied heavily on liquor sales, Hinkel became a key company executive while still in his teens.

After toiling for the grocery chain for more than a decade, Hinkel opened his own liquor house at 461 Pearl Avenue in 1892. This move may have been triggered by his 1889 marriage to Minerva Marie, “Minnie” Willschlager (1870-1927). The couple would produce three children, two girls and a boy. With a growing family Matt likely felt the need for more income.

Under Hinkel’s adept managerial hand, his liquor business grew and flourished. The need for more space apparently prompted a move to 1778 25th Street in 1906 and subsequently and finally in 1909 to 814-820 Prospect Avenue SE. It is difficult to assess Hinkel’s marketing strategies. He apparently did not advertise widely and artifacts from his trade are few. I have been able only to locate a metal jug engraved “Hinkel’s Pure Rye,” the artifact that first put me onto the track of this whiskey man’s story. The jug likely was meant for use on a bar where it would have held water or tea for “cutting” whiskey.

Under Hinkel’s adept managerial hand, his liquor business grew and flourished. The need for more space apparently prompted a move to 1778 25th Street in 1906 and subsequently and finally in 1909 to 814-820 Prospect Avenue SE. It is difficult to assess Hinkel’s marketing strategies. He apparently did not advertise widely and artifacts from his trade are few. I have been able only to locate a metal jug engraved “Hinkel’s Pure Rye,” the artifact that first put me onto the track of this whiskey man’s story. The jug likely was meant for use on a bar where it would have held water or tea for “cutting” whiskey.

When and how Hinkel honed his passion for sports is unclear. His first foray seems to have been into baseball. In 1912, he sponsored an amateur team known as Matt Hinkel’s Champions. When offered a chance to have a professional franchise in the newly formed Columbia League, he jumped at it, hiring a manager and negotiating a contract with the owner of Luna Park on the outskirts of Cleveland for the erection of a 20,000 seat baseball stadium. When the new league imploded without a single game being played, Hinkel must have been devastated, but retained his interest in baseball, befriending the great Ty Cobb and becoming his hunting partner.

Hinkel would make his mark in fisticuffs, gaining recognition as both an impresario of boxing matches and a referee. His breakout event was arranging a 15-round featherweight championship bout on Labor Day 1916 at Cedar Point, Ohio, shown below. The match pitted Johnny Kilbane, left, the title-holder and Cleveland native, and George Chaney of Baltimore, called “The Knockout King of Fistiana.” The Plain Dealer opined: “Twenty thousand American dollars must pass through the gates of Cedar Point…before…[the bout] is a financial success.” The crowds came and watched their Local Hero dispatch Chaney in three rounds. Much of the credit — and profits — went to Hinkel.

Hinkel would make his mark in fisticuffs, gaining recognition as both an impresario of boxing matches and a referee. His breakout event was arranging a 15-round featherweight championship bout on Labor Day 1916 at Cedar Point, Ohio, shown below. The match pitted Johnny Kilbane, left, the title-holder and Cleveland native, and George Chaney of Baltimore, called “The Knockout King of Fistiana.” The Plain Dealer opined: “Twenty thousand American dollars must pass through the gates of Cedar Point…before…[the bout] is a financial success.” The crowds came and watched their Local Hero dispatch Chaney in three rounds. Much of the credit — and profits — went to Hinkel. |

| Cedar Point Pavilion |

Soon Hinkel was being compared to the famous New York fight promoter, Tex Rickard. His reputation as a referee also was growing. In September 1917, he promoted a heavyweight battle in Canton, Ohio, between two heavyweight contenders, Fred Fulton, known as the “Pugnacious Plasterer,” and Carl Morris, “The Oklahoma White Hope.” Despite having thousands of dollars to lose, Hinkel stopped the fight in the third round after Morris, a brawler, repeatedly hit Fulton with low blows and refused to stop. Morris was disqualified and Fulton declared the winner.

A Philadelphia sports writer covering the match marveled at Hinkel’s courage: “When he disqualified Morris he risked his reputation and got away with it. The decision was greeted with cheers and Matt was called back to the ring for a further ovation. He is stronger than ever with the boxing fans, for he proved yesterday that he not only is a capable, but fearless referee. He is the kind of man we need in Philadelphia.”

A newspaper in Edmonton Canada identified him as Cleveland’s “millionaire boxing referee.” A Duluth, Minnesota, daily hailed him as “one of the best ring arbiters in the country.” Sportswriters around the country regarded him as a guru on the fight game and hung on his words. Newspapers from El Paso to Milwaukee reported a speech Hinkel gave in July 1917 in which he declared that all championship fights should be scheduled for twenty rounds and titleholders should not participate in shorter prize fights even though they might be lucrative.

Shown above is Hinkel refereeing perhaps the most famous bout of his ring career. Held at the Olympic Arena in Brooklyn, Ohio, the 1924 fight drew national attention as Harry Greb (left), the world’s middleweight champion, fought Gene Tunney, the American light-heavyweight champion. Two years earlier Greb had given Tunney, later world heavyweight champion, the only defeat of his career. The rematch went ten rounds, called a “see-saw” affair, and the judges declared it a no-decision. Hinkel told the press that if he had been permitted to vote he would have declared the contest a draw.

Despite the rigors of running his liquor business and promoting the fight game, Hinkel had the energy to manage other Cleveland enterprises. He was president and treasurer of the Art Electrotype Foundry Company, an outfit that made printing plates. He also was president and treasurer of the Smith Form-a-Truck Company, an early entry into the burgeoning automotive field, and was vice president of the Arts Photo Paper Company. To these activities must be added his work as a civic activist and participation in the Elks, Moose and Cleveland’s Tuxedo Club.

Despite the rigors of running his liquor business and promoting the fight game, Hinkel had the energy to manage other Cleveland enterprises. He was president and treasurer of the Art Electrotype Foundry Company, an outfit that made printing plates. He also was president and treasurer of the Smith Form-a-Truck Company, an early entry into the burgeoning automotive field, and was vice president of the Arts Photo Paper Company. To these activities must be added his work as a civic activist and participation in the Elks, Moose and Cleveland’s Tuxedo Club. |

| Matt Hinkel |

With the coming of statewide prohibition, Hinkel was forced to shut down his liquor house in 1919 after 27 years in business. By this time he was 52 years old and could rely on his other enterprises for activity and revenue. Moreover, the ensuing years would be among his most active in the fight game. Yet Matt seemed to sense that National Prohibition would end before long and kept one hand in the liquor trade.

|

| George Remus |

That pitted the Cleveland fight promoter against one of America’s most dangerous bootleggers, George Remus. Shown here, Remus, a lawyer, saw that his criminal clients were becoming wealthy very quickly through the illegal production and distribution of alcoholic beverages. Remus read the fine print in the Volstead Act and found a loophole that allowed him to buy distilleries to produce and sell bonded liquor for medicinal purposes, under government license. His employees, eventually numbering 3,000, then would hijack his own liquor so that he could sell it illegally. The scheme realized $40 million in less than three years. When eventually caught and sentenced to prison in 1925, Remus’ estranged wife, Imogene, took the opportunity to sell off his whiskey.

Hinkel purchased most of the Remus stash, including 3,000 barrels of whiskey from the Pogue Distillery in Maysville, Kentucky. The bootlegger’s attempt to “rescue” that whiskey before he went to jail had been thwarted by a judge’s order, likely initiated by the Clevelander. The Pogue whiskey became Hinkel’s. Rather than menacing Matt, Remus took his revenge on Imogene. Released from jail, he shot her down on a Cincinnati street and beat a murder rap by pleading insanity.

Hinkel purchased most of the Remus stash, including 3,000 barrels of whiskey from the Pogue Distillery in Maysville, Kentucky. The bootlegger’s attempt to “rescue” that whiskey before he went to jail had been thwarted by a judge’s order, likely initiated by the Clevelander. The Pogue whiskey became Hinkel’s. Rather than menacing Matt, Remus took his revenge on Imogene. Released from jail, he shot her down on a Cincinnati street and beat a murder rap by pleading insanity.

My guess is that Hinkel was able to continue selling this whiskey through the authorized “medicinal” channels during the remainder of the 1920s and into the 1930s. In the mid-1930s as National Prohibition was being rescinded, Hinkel would have found a strong demand for any remaining stocks. With Repeal, however, he did not revive his Cleveland liquor house, possibly because of declining health.

On September 19, 1936, Hinkel, age 69, suffered a heart attack and died. He was survived by his second wife, Bessie (Hayes) Hinkel and his three children. Following a funeral in his home, he was interred in the Lake Park Cemetery, Rocky River, Ohio. His gravestone is shown here.

From a 12-year-old office boy, Matt Hinkel had risen to the ranks of Cleveland millionaires by dint of his intelligence, hard work, and chosen occupation selling liquor. Perhaps more important, he had helped put his home town and Northeastern Ohio into the front ranks of America’s sports by his promotion of nationally noted boxing matches.

Note: This vignette has been drawn from a wide range of sources. Two principal ones were brief biographies in “Men of Ohio” issued in 1914 by the Cleveland Leader and Cleveland News newspapers and “A History of Cleveland and Its Environs,” authored by Elroy McKendree Avery and issued in 1918 by Lewis Publishing Co. Subsequent to this posting, in August 2022 the Hinkel shot glass shown here came to light and has been added.

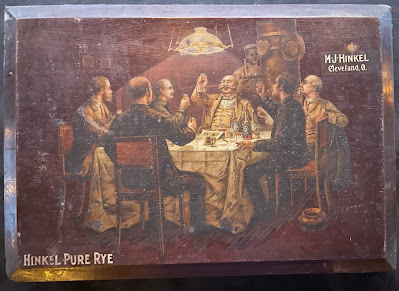

Note: This vignette has been drawn from a wide range of sources. Two principal ones were brief biographies in “Men of Ohio” issued in 1914 by the Cleveland Leader and Cleveland News newspapers and “A History of Cleveland and Its Environs,” authored by Elroy McKendree Avery and issued in 1918 by Lewis Publishing Co. Subsequent to this posting, in August 2022 the Hinkel shot glass shown here came to light and has been added.Addendum: Noting my comment above about my problems finding whiskey artifacts from Matt Hinkel, Jack Past of Phoenix, Arizona, was kind enough to send along the saloon sign below. It was purchased some time ago by his now diseased father, Dr. Si Past of Dayton, Ohio, a collector. I had never before seen it. The sign is a marvel and my great thanks to Atty. Past for allowing me to replicate it below.

No comments:

Post a Comment